AN UPRIGHT MAN

By Stanley Rice 2014

An upright man—there is my story. Every image we

have of Edd Hicks is stern and upright, as if by his very glance he

could bring order to the world. In almost every image he is slightly

frowning, not in sadness or anger, but with a sense of control of his

life. In some images, such as the one on the homepage, he is just

slightly smiling. Since he was born in 1879 in Indian Territory, not

far from Oologah in what is now northeastern Oklahoma, you might think

that the reason for his stern expression was that he had to sit

motionless for a daguerrotype. But most of the images are from the

post-Instamatic age. No, it was because Edd was a serious man, as right

as right can be. He was much more serious than the boy who was born

across the creek on Dog Iron Ranch the same year, the boy who kept

getting into trouble, a boy Edd used to hang around on the streets of

Oologah with, a boy named Will Rogers.

In this story, we will try to find out why Edd was

so serious.

Edd Hicks was a member of the Cherokee Nation in

Indian Territory. The Cherokee tribe had experienced two tumultuous

centuries (see Nancy Ward: Cherokee Ancestor of Edd Hicks and The Trail

of Tears: How Edd’s Family Came to Indian Territory). By the end of the

nineteenth century, the Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory had overcome

most of its chaos. It had flourishing cities, farms, and schools. But

more chaos was on the way. The United States now wanted to annex Indian

Territory as part of the new state of Oklahoma.

In addition to what was going on in the Cherokee

Nation, there was plenty of chaos in Edd’s immediate ancestry.

A Chaotic Family

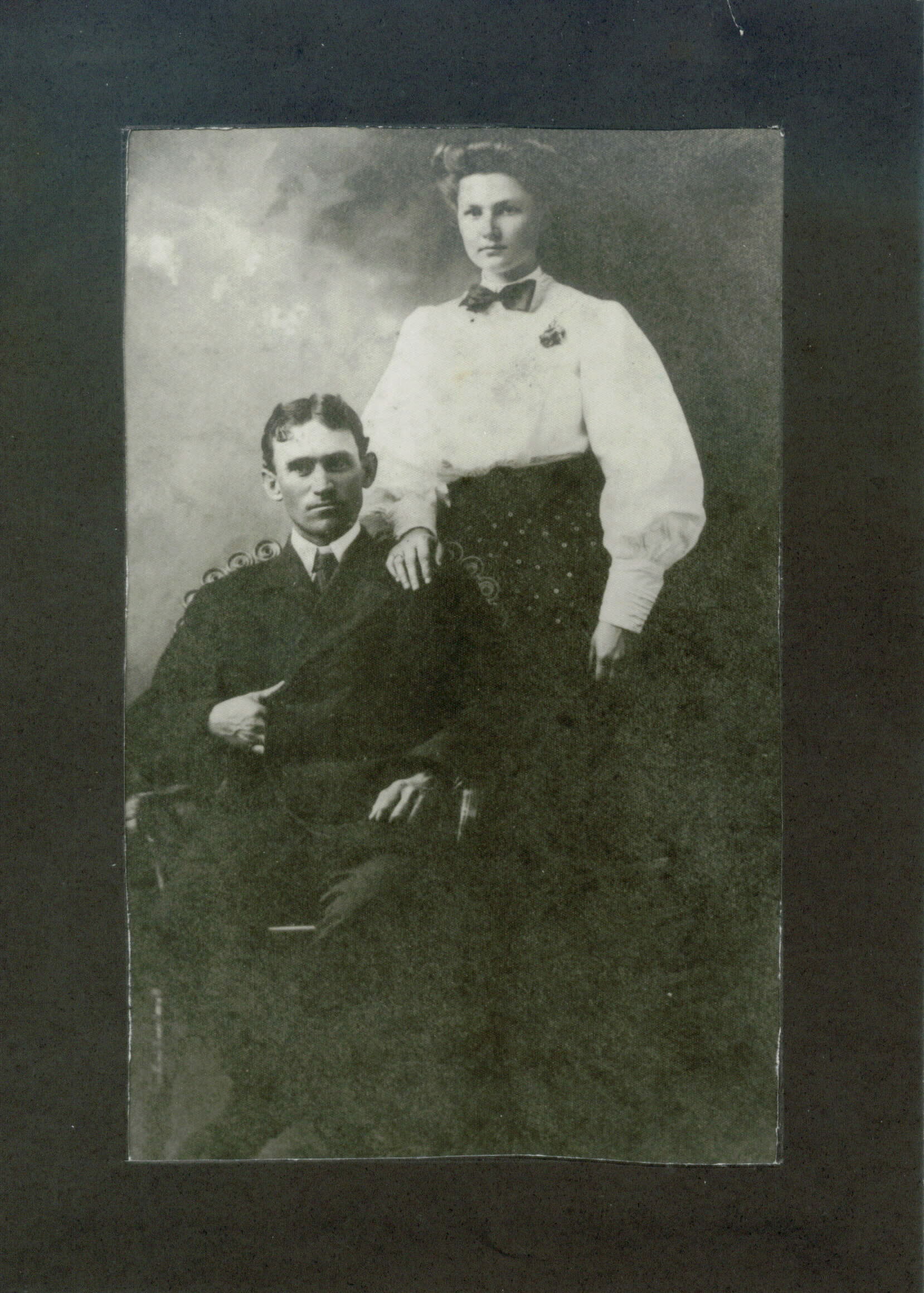

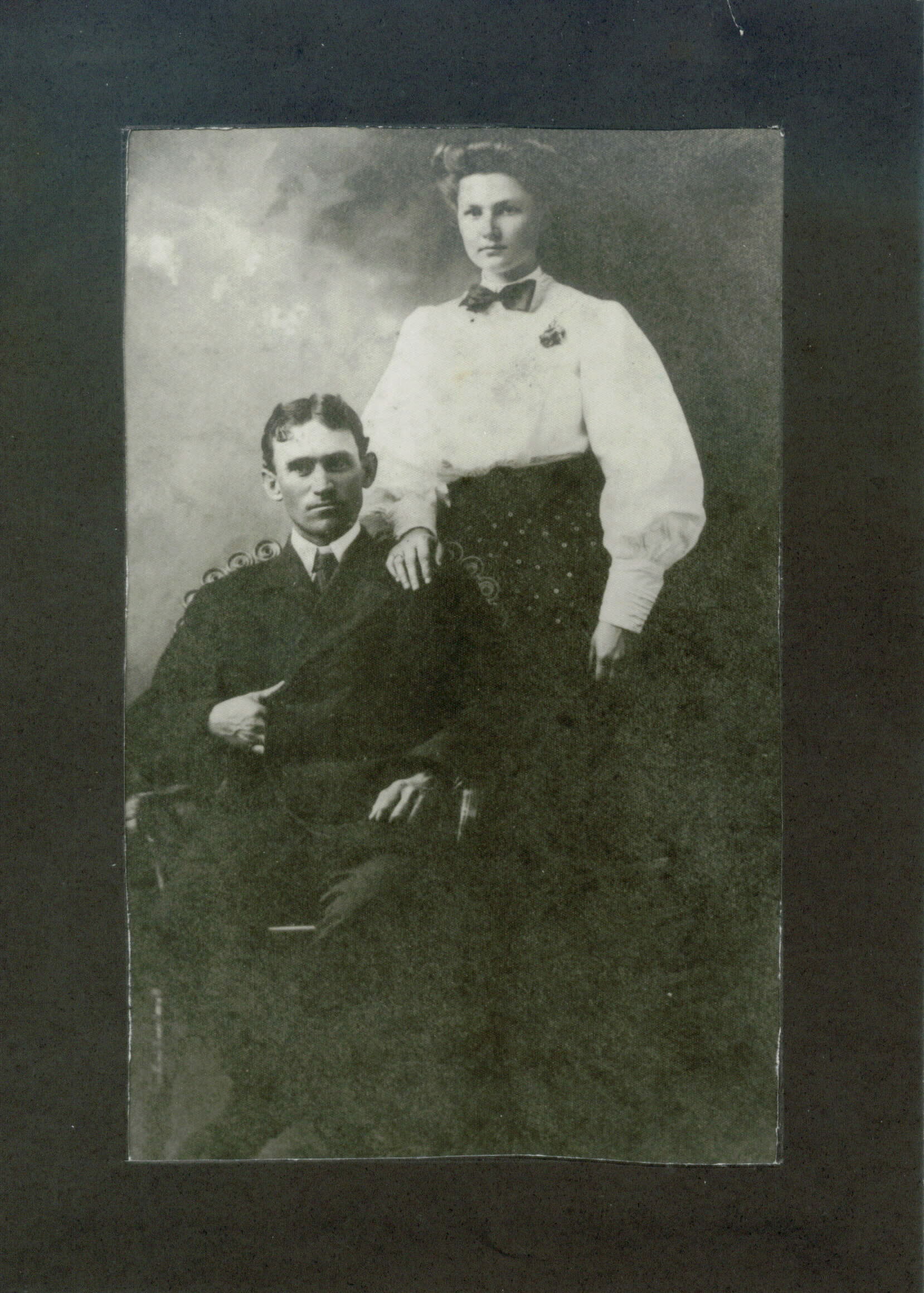

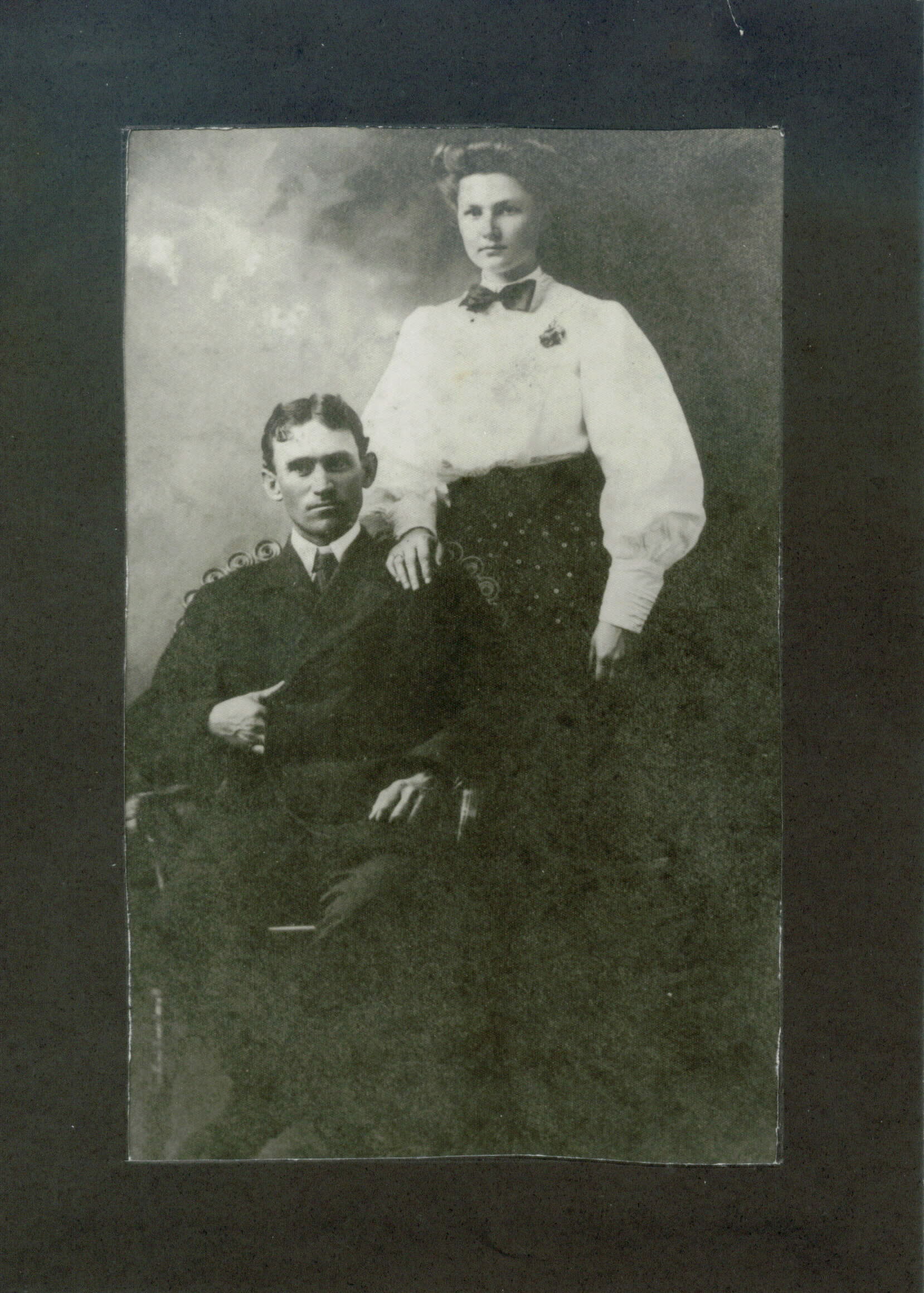

In 1907, the same year as Oklahoma statehood, Edd

was engaged to Mary Carter. In his engagement portrait with her, he has

a satisfiedly serious look, confident that he was about to establish a

family. As he and Mary rode into town in a carriage to get married,

they were stopped by Mary’s brothers, armed and on horseback. They

demanded that she return home with them. Edd may or may not have known

that this might happen, but either way, he was prepared. He told Mary

that her decision, right then and there, would be final. There would be

no negotiation or hesitation. No attempts to patch up differences. Edd

did not apparently say, “Now, boys, can’t we all just get along here?”

Mary went home with her brothers. Edd must have been crushed, but he

never doubted that he had made the right decision. His setback was

temporary. Two years later, he married a woman, Estella Leona Huston,

whom he had met in the store in Chelsea where he was the butcher, a

store he had started with his brothers about 1890.

But this raises more questions—what was it about Edd Hicks that made a

rural Oklahoma farm family consider him objectionable as an in-law? As

far as any of his descendants know, there was nothing personally

objectionable about him personally. Near as we can figure, it must have

had something to do with the family from which he came. And this might

bring us to another reason for his uprightness: his reaction against

his family. Here are some possibilities.

Edd’s great-grandmother.

Edd’s great-grandmother was Elizabeth Hilderbrand (born 1801), a

great-granddaughter of Nancy Ward. She married James Pettit and they had

a farm in the Cherokee Nation prior to the Trail of Tears. Their three

children were Andrew (born 1828), Minerva (born 1830), and William (born

1832 or 1833). Elizabeth Hilderbrand Pettit and her three children were

on the Trail of Tears, but James Pettit was not with them. Here is why.

Some white men took Cherokee wives and raised

Cherokee families, but also had white wives and white families. This may

have been what happened with Nancy and Bryant Ward. Bryant and Nancy

had a daughter, but Bryant also had a white family in South Carolina. By

the early nineteenth century the Cherokee Council considered this to be

bigamy. So when Elizabeth Pettit found out in 1829 that her husband

James had a white family in Missouri, she brought suit against him. The

Council found in her favor, and she kept the kids, the farm, and

everything else. Not that it made much difference; within a few years,

she was on the Trail of Tears, with only what she could carry. Elizabeth

Pettit was the first and only woman to sue her husband for bigamy in

the Cherokee Nation prior to the Trail of Tears.

When she got to Indian Territory, Elizabeth Pettit

remarried, first to Daniel Ward, then to Robert Armstrong. Elizabeth

Armstrong died in 1877 and is buried in the Ft. Gibson Cherokee Citizens

Cemetery, alongside her son William.

Therefore, for several generations up to and

including his grandfather’s, Edd’s family had a history of marital

chaos. It seems reasonable that Edd wanted nothing to do with the other

branches of his family from those earlier days. Regarding the

Hilderbrand family, Edd’s daughter Nina recalled him saying, “They’re no

kin of mine,” which, said Nina, probably meant that they were.

Edd’s father.

Not much is known about Edd’s father, Andrew Jackson Hicks, except that

he was a chaser of dreams. His marriage was not chaotic; he married

Mary Adelide Franklin, and was married to her for the rest of his life.

Andrew died, when Edd was 26, of pneumonia that he got while searching

for lost Indian gold. According to family legend, Andrew kept some gold

hidden in a creek bank, and when, after his death, somebody came

looking for it, the ghost of Andrew Hicks came riding on his white

horse. Was Edd determined to never be a chaser of dreams and source of

embarrassing legends like his father?

There was also confusion about Edd’s Cherokee blood

quantum (and therefore, that of all his descendants). Was U-s-quv-ne a

fullblood Cherokee? Many citizens of the Cherokee Nation, back in the

east, were partly white. Chief John Ross was himself only one-eighth

Cherokee. Minerva Pettit was part Cherokee. Bryan Ward, and probably

Joseph L. Martin, were white, making Nancy Martin one-quarter blood

quantum. But Michael Hildebrand might have been part Cherokee. And

Edd’s mother, Mary Franklin, looked very much like a Cherokee in one of

her early photographs. She lived in Tennessee, where some Cherokees had

managed to stay after the Trail of Tears. Edd signed the Dawes Roll of

Cherokee citizens, and listed his blood quantum as one-sixteenth. This

siblings listed other, and larger, blood quantum figures. They cannot

all be right. The siblings all had the same blood quantum, but listed

different amounts.

Edd made sure his children knew about their Cherokee

ancestry. My Mom (Nina) told me that on hot days he would sit in the

doorway, where the breeze was greatest, and sing Cherokee songs. The

youngest kids (Nina, Jack, Bill) thought they sounded so strange and

laughed at him. Edd tried to teach Cherokee language to the youngest

kids, but they thought it was ridiculous, and he gave up. Edd had a

Cherokee name, Tsi-s-qua, but this is the word for “little creature,”

so it must have been a childhood nickname, rather than a serious name,

that his father (or grandfather) had given him. The only Cherokee

language the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Edd Hicks know is

from books and websites.

Edd’s sister.

Andrew and Mary had the following children, with their Dawes Commission

enrollment numbers (for more information, see the Partial Family Tree):

Edd (13,250); Serena (13,540); Frank (12,928); Lon (12,927); and Amelia

(12,929). Andrew’s enrollment number was 12,926. Two other children,

Annie and Alvie, died in 1896, before the enrollment began (for their

story, see the Partial Family Tree). It appears that Serena (whose name

is spelled in lots of ways, such as Surrener) was not as wild as

Minerva but did not have marital stability. She was married several

times.

Edd’s brother.

Edd also undoubtedly reacted against his brother. The photo we have of

Lon Hicks shows an old man who had a slight grin that hid a secret. He

was the trickster who could talk you into giving him everything you had

and then slipping away in the night. Family accounts differ as to what

he did. One account says that he ran the store where Edd was the

butcher, and that, one day, he was gone—to Las Vegas, with the store’s

till. Another account says that he talked Edd into selling his Cherokee

allotment land for a dollar an acre, far less than its value, then sold

the land without telling how much he got for it.

Either way, it was clear that Lon was the one who

wanted other people to do the work, while Edd had decided that he would

do everything himself. Everywhere he lived, as he moved frequently, Edd

grew his own food and milked his own cows. In at least one case, at

Salina (on land now flooded by Lake Oolagah), he built the house

himself. Until he was old, none of his houses had electricity. He and

Stella raised chickens, and fed a large family on eggs and milk and

vegetables and meat, all from their own farm. Since there was no

refrigeration, whatever they could not eat on any day was loaded onto

the wagon and pulled to the general store by the mules, Kate and Beck,

to be traded for the few food items, such as flour and salt, that Edd

did not raise himself. They always sold the cream. This was how Edd had

determined to live, while Lon was in Las Vegas. And it was clear which

way of living was more successful. Edd’s family always had food during

the Great Depression, even though the little money Edd had in the bank

was lost overnight. Lon died indigent, in a county nursing home in Los

Angeles, and was buried in a common grave.

And this tells us exactly what Edd was like. He

lived his entire life, every moment of it, creating a space of peaceful

order. Build a house and a barn, plow a farm, raise food, send the kids

to school. Edd insisted on a life that was as right-angled as the

corners of the houses he built. Frequently, circumstances beyond his

control made this impossible. I do not remember all of those

circumstances. In one instance it was because they lived near a

relative who turned out to be very demanding. (This was probably at the

Slocter place. One of Serena Heape’s daughters, Clara, married a man

named Slocter.) The last straw was when the woman (Clara Slocter?)

objected to Edd cutting away some wild grape vines. When something

happened that would make his idealistic life impossible, Edd would move

the whole family to a new place. It appears that he never for a moment

considered staying and trying to patch up a compromise or to tolerate a

dilution of his principles. He moved from one Promised Land to another

every five to ten years.

A Hard and Upright Life

Edd’s life involved a lot of hard work. The kids

also spent many hours of work to keep the family fed. The only way to

have food in the winter was to can it, lots of it. While it may have

been easy enough to boil and can tomatoes, they had to snap the beans

and remove the fibers along the edge before canning them. Raising the

food was a lot of work too. The kids would spend hours picking Colorado

potato beetles off of the tomato and potato plants and putting them in

tin cans, where they would be killed by hot water Stella brought from

the kitchen. They had no washing machines. Clothes dried on the

clothesline but had to be ironed (there was no permanent press in those

days) with irons heated on a wood stove, a task that took the two girls

Clara and Nina many hours each week. Do the math. Eight kids.

Edd was also religiously upright. When the famous

preacher Billy Sunday came through, he had dinner at Edd’s house and

talked with him a few hours. We will never know what they discussed,

but we can be sure that they figured out that the world around them,

near and far, was a black-and-white patchwork of good and evil, with no

indecisive grayness in between. Edd was also, more than once, the head

of the school board. Once, in a one-room schoolhouse (as all of them

were in rural Oklahoma), a young female teacher had kept a particularly

handsome male student in the classroom while making all the other

students play outside. Once again, we do not know what happened, but

Edd talked to the teacher, who soon vanished.

It almost seemed as if the world that surrounded Edd

obeyed him. Crops grew. Cows gave milk. And his children lived, most of

them. His firstborn, Clifford, died after a few months, perhaps of a

birth defect. His second-born, a son named Herb, lived well into

adulthood, but was killed in a gas field explosion. His ninth child,

Floyd, a gentle blond boy, died at age five of a bacterial disease. But

the others lived. Almost miraculously, all of his sons fought in World

War Two and not only survived but were never harmed. Maybe God listened

to Billy Sunday and to Edd.

Edd and Stella did not have much of what we consider

to be essential today. I do not refer only to electricity, but to

things such as health insurance. When their daughter Nina (my Mom) got

poison ivy all over her face, and lethal infection was a real

possibility, Edd went into town and bought ointment (the kind that

would now be considered toxic) and applied it to her face with a

chicken feather. Edd and Stella’s success at making a good life in no

way shows such things as health insurance to be unnecessary. If they

could have afforded health insurance, it is nearly certain that

Clifford and Floyd would have survived. If there had been workplace

safety rules, the explosion that killed Herbert might not have happened.

The End of Edd’s Life

Edd was accustomed to having his body obey his will,

and it did right up to the end of his life. But he was cantankerous

when he was older. Some of the grandchildren who knew him considered it

a game to get away from him, as he was always ready to administer

corporal punishment. It was not merely their misbehavior, real or

imagined, that got him riled up. It was also his irritation at seeing

his own body disintegrate.

Edd had a stroke in 1959. As the stroke was

beginning, he was getting dressed to go to the hospital. He fainted

while getting dressed, and Stella had to help him and clean him up. It

can safely be said that he hated being helpless.

And, as you might expect from a larger-than-life

person, there is some Edd Hicks mythology that has survived. According

to two of his children (Clara and Bill) who witnessed his death, what

appeared to be a ball of fire moved under his hospital bed and out the

window at his last breath. Though some consider this a miracle, the

possibility that it was just automobile headlights from outside

reflecting on a mirror cannot be discounted. Stella, who was resting at

home, did not see it.

Stella outlived Edd by two decades. When she was

very old, she lived alone in a small house on Cherokee Street in

Claremore, a house that was later torn down, in a block that is now

being made into a commercial property. Her Social Security was a mere

pittance, since Edd’s work did not involve payroll taxes or payrolls at

all. She received welfare money. One day about 1968, when most of her

children were together in her living room, they were talking about how

terrible the people were who were on welfare. Stella piped up,

emotionally, that welfare had been a blessing to her. All her children

instantly said that she deserved it, because she had worked hard all of

her life. They had been condemning those who used welfare as an excuse

to not work.

The next generation

The generation of Edd and Stella’s children grew up

with some of the same virtues. But Edd was so staunchly right that, in

some ways, his children reacted against his heavy burden of virtue.

It was evident in many small ways. Edd would never

have allowed what he considered an unclean word to pass his lips. His

children, when growing up, or when in his presence as adults, also

spoke cleanly. But get “The Boys” together by themselves, and the

language just ripped. Laughter was as abundant in them as it was

restrained in Edd’s character. I am trying to imagine how Edd would

ever have done what his son Dick did, entertaining the next generation

by making a squeaking noise with his dentures.

It was also evident in larger ways. To Edd, his

family was sacrosanct. Divorce was unthinkable. It probably never

occurred to Edd or Stella. We know of no reason they might have been

dissatisfied with each other. But the fact that they needed each other

for economic survival must have helped. In the next generation, there

were three divorces which, out of seven adult children, was slightly

below the national average. The oldest surviving son, Roy, married a

woman, Lola Mae, who was already pregnant by another man. The child,

who went by the name Roy Hicks, lived in Oologah. But Roy and Lola Mae

divorced and Roy married Maxine. (Native American blood quantum here

gets even more complex, since both Roy and Maxine were descended along

separate lines from Minerva Petit, whose last husband was Lewis Hicks.)

A middle son, Dick, married Betty and had four sons. Eventually he

divorced Betty and married Barbara. The youngest son, Bill, married

Lillian, and had two children before eventually divorcing her and

marrying Lucille. I, for one, was raised to think that these couples

just had irreconcilable differences; I was never encouraged to dislike

the former spouses of my three uncles, though I only met one of them.

What stories this next generation had, both at home

and in the War. This essay, about Edd, cannot include their stories,

which will be placed separately on this website.

The Legacy of Edd and

Stella

It is clear that the lives of Edd and Stella

continue to live in their grandchildren, in both good and bad ways

(mostly good). As for how their legacy continues in their

great-grandchildren, they will have to write the chapter themselves.

The most obvious way is in virtue. Though Edd and

Stella’s children and grandchildren have had many imperfections, it is

clear that they are above the national average in leading lives of

goodness. No criminals, no abusers, and all (to my knowledge)

passionately hard workers. By a combination of good luck and hard work,

none are dependent on public assistance. Most believe that hard work

will keep you from financial disaster, but they also know that

(especially during a recession) luck has also been a reason that we are

not a welfare family.

Edd and Stella’s grandchildren, like their children,

have also been frugal. Now this is a term that is not popular in

America today. Being frugal is nearly the equivalent of being

unpatriotic. In order to help corporations lift the economy out of

recession, we are supposed to be, as much as possible, consumers. That

is, buy things even if you don’t have the money, then throw them away

and buy new things. Edd and Stella lived frugally, before and during

and after the Great Depression, and not just because they did not have

very much spare money. They believed that you could enjoy life just as

much with few possessions as with many, and they were right. It made

things a bit austere, maybe even grim—as far as I know, they never had

a Victrola or a radio. Clothes and quilts were home-made (by Stella),

although each child got a new pair of shoes whenever they needed them.

Just one, as I understand. Their grandchildren are much more wasteful,

but less so than the average American. In at least one case (me), the

decision was made that the nearly six hundred dollars a year for cable

TV was better spent elsewhere. Edd and Stella never took on debt.

Edd and Stella’s family did spend their resources on

some pleasures, but only for important events, such as Christmas. In

rural Oklahoma during the early twentieth century, you could not just

go and buy a Christmas tree. The Christmas tree was a cedar bush,

probably cut by Edd himself. There were a few presents. But, as my

mother recalled, the main event was to come downstairs on Christmas

morning and find that each child’s plate had an orange on it. At the

time, oranges were rare in rural Oklahoma stores.

One bad legacy is a lingering dislike of races other

than white and Native American. It is not a general white racism, since

the whole family is only too aware of its mixed ancestry—and proud of

it. Hatred of black people, however, was very openly articulated by the

generation of Edd and Stella’s children. They must have gotten it from

Edd and Stella. None of them, however, would have participated in

violence against blacks. (Somehow my Mom ended up inheriting a gavel

that was used at KKK meetings, but it came from outside the family.)

Then sometime in the early 1980s, Edd and Stella’s children just

stopped using the N word very much, and stopped saying much about black

people. Did they have a change of heart, or did they just see that

racism was a vestige of the past? The grandchildren still have little

tatters of racism, but this attitude is clearly dying away.

But if that is the worst thing you can say about the

legacy of Edd and Stella Hicks, it still leaves them as a major force

for good in the world in their time. If you can divide the people of

the world into the Builders and the Destroyers, it is clear that Edd

and Stella were passionate Builders, a state of mind that has continued

in, as far as I am aware, all of their descendants. In those cases

where other people or families, who have come into contact with ours

through marriage, have acted in a destructive fashion (and there are

lots of stories about this), everyone in our family has marveled that

such destructiveness was even thinkable. We descendants of Edd and

Stella can hardly even imagine the destructive attitude that so many

other people have. And that tells you what kind of people we are.

Epilogue

So much of our history has been lost. We are not one

of those families in which journals were kept. The generation of Edd

and Stella’s grandchildren are not pleased at how few of the

photographs in the albums had names and dates on them. Fortunately,

many people in the photos were unmistakable, because of Edd’s stern

satisfaction, Lon’s avuncular but mischievous smile, the sharp faces of

Roy and Dick, Bill’s impish grin, and so on. Of course we figured out

who Kate and Beck were, since they were the only two mules in the

photos. Edd and Stella’s children did not like to talk a lot to their

children about their lives. My Mom mentioned that, one day about 1998,

most of the siblings had gotten together for lunch at her apartment in

Claremore. “The boys” started sharing World War Two stories which, Mom

said, they seldom talked about. I wish I had been there and heard them.

But no one now alive was there. We have to make the best use that we

can of the little fragments we have, like little pieces of skeleton of

a great ancient beast that happened to be preserved in a fossil layer.

And that is what we are trying to do on this website, so that all of

their descendants can share and read the stories that they remember,

and that the world can get a glimpse of life in rural Oklahoma in the

last century.

I invite all descendants of Edd and Stella to send

or tell their stories to me, and, with their permission (and my the

editorial work as a professional writer), I will post them on this

website in upcoming months and years.